Georgia: Make Elections Fair and Accessible by Keeping Polling Places Open

Even seemingly small changes negatively affect voter turnout, especially in communities of color.

Overview

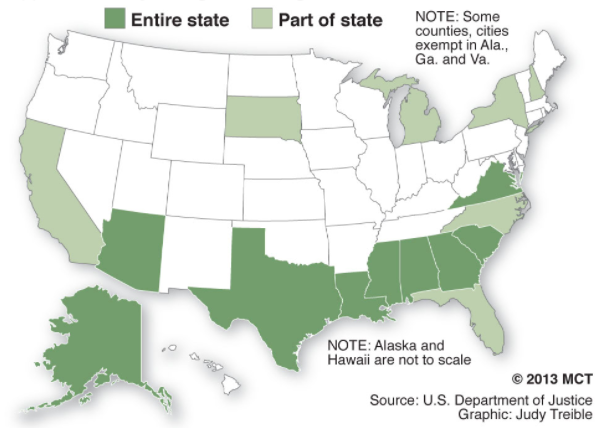

The Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) dismantled key components of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). Originally passed to address systemic discrimination against non-white voters, especially in the South, the Voting Rights Act required certain jurisdictions to “preclear” (or pre-approve) any change to election law with the United States Department of Justice or a three-judge district court.[i] The Shelby County decision found that the coverage formula — the mechanism in the VRA that determined which jurisdictions required federal scrutiny via preclearance — was outdated and, therefore, unconstitutional.[ii] Previously covered jurisdictions that had been required to preclear changes to their election laws were now able to change their election policies and laws at will.

Since Shelby County, elections officials across the country — and specifically in Georgia — have closed and consolidated hundreds of polling places.[iii]

One study found that nationwide, since Shelby County, voters in counties once covered by the VRA had at least 868 fewer places to cast ballots in the 2016 presidential election than they did in past elections, a 16 percent reduction.

[iv] Although local officials have justified the closures as cost-saving measures, many polling places that were closed disproportionately affected Black and Latino voters and caused chaos on Election Day.

Why it matters

Poll closures and consolidations have a significant effect on voters. Fewer polling places often means longer distances for voters to travel, longer lines, and voter confusion — all of which leads to fewer people voting. When these closures occur in jurisdictions with a history of voting discrimination, people of color can be disproportionately impacted. What makes poll closures especially malicious is that there is no recourse to get your vote back. Poll closures often occur quietly and at the last minute.[v] Even when the closures are clearly discriminatory, there are no do-overs to account for the ballots that weren’t cast because of poll closures.

The Supreme Court’s decision to nullify the Voting Rights Act’s coverage formula opened the door to the return of voter discrimination at the polls.

As Justice Ginsburg said in her dissent in the Shelby County case, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”[vi]

Our position

Let America Vote believes that voters should be able to vote in polling places that are accessible to where they live. Polling place closures and consolidations can cause long lines, create voter confusion, and ultimately deter people from voting. Elections officials should conduct a careful impact analysis, receiving community input before closing polling places. Further, any and all changes should be clearly communicated to voters in the jurisdiction well in advance of an election. Any polling closure or consolidation that is discriminatory or that happens at the last minute should not be allowed. Congress should also act to restore the Voting Rights Act in full and protect access to the ballot for every American.

Background

Voter discrimination has a long history in Georgia. Georgia was one of the nine states wholly-covered by the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[vii] Since the VRA’s passage in 1965, federal authorities have rejected 177 proposed changes to Georgia election law because the changes were discriminatory.[viii] Without the full protection of the VRA, Georgia voters are subject to the actions of public officials who now have complete power to determine the time, place, and manner of Georgia elections, without federal oversight.

Today, Georgia is one of the worst offenders when it comes to voter suppression. It was one of the first states, along with Indiana, to enact a “strict” voter ID law in 2008.[iv] Also, this year, the state purged over 500,000 voters from the rolls, and sent removal notices to thousands of voters who moved within the same county.

Who’s Affected

Poll closures and consolidations affect every member of the community in which they take place. A recent study on the effect of poll closures in the 2014 election found that “[voters] who were assigned to a new polling location were less likely to go to the polls on Election Day in 2014 and more likely to abstain than those who kept their polling location.”[viii]

However, some voters feel the effects more than others. Poll closures can place an undue burden on people of color, who in many cities are statistically less likely to have accessible public transportation or vehicles.[xiv] Additionally a study found that “Democrats were more likely to be affected by polling location changes than Republicans.”[xv]

Not all poll closures are corrupt, but election officials, armed with this knowledge, can use poll closures to manipulate vote accessibility. Georgia has several clear examples of poll closures that unfairly affected black voters.

Community Narrative: Hancock County and Irwin County

In 2015 in Hancock County, about 100 miles southeast of Atlanta, the Board of Elections planned to close 9 of its 10 voting precincts. Their plan would have left one remaining polling place in downtown Sparta, Hancock County’s county seat and a city with a deep racial divide.[xvi] This would have caused some precincts to be up to 17 miles from the one remaining precinct, creating an unfair travel burden to the county’s majority-black precincts. The NAACP and other advocacy groups successfully argued that the board’s plan would disenfranchise rural blacks who could not travel such far distances to vote, and the Board of Elections decided to only close one polling place instead of nine.

In rural Irwin County, local activists warned the county’s Board of Elections and Registration not to move forward with a proposed plan to cut the number of polling places.

One proposal the Board was considering would have shut down six polling places, including one in the predominantly black city of Ocilla. The two remaining polling places would have been located in Irwinville, which is 96 percent white and home to the Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site.[xvii] The Board’s proposal ran counter to a plan suggested by the nonpartisan Association of County Commissioners, which recommended keeping at least one polling place in or near Ocilla.[xviii] After pressure from the ACLU of Georgia and other community advocates, the Board decided to drop both controversial proposals and adopt a plan that kept a polling place open in Ocilla.[xiv]

Expert Insight: Justin Levitt

Let America Vote spoke with Loyola Law School Professor Justin Levitt about poll closures. Levitt, former Deputy Assistant Attorney General and a nationally recognized scholar of constitutional law, stressed that communication is key when changing polling places. “Regardless of what you end up doing with polling places, if you don’t let people know about it, that’s a recipe for disaster.” In addition to effective communication about changes, Levitt highlighted that each polling change is unique. “Whenever you close a polling place, there has to be attention paid to how you handle the increased volume at each one… You’ve got to pay attention to where the polling place you’re closing was, and where the polling places that you have remaining open are. If you close the polling place that’s located in the senior center, you’ve got to make sure the seniors are able to get somewhere where they can actually vote. If you close the polling place in the African American neighborhood, you better make sure they are able to get somewhere where they can actually vote… It takes real attention to each polling place.”

However, Levitt argued that poll closures are not inherently bad. In fact, poll closures can be an avenue toward improving the voter experience if done right. For example, a change from having many polling locations scattered in specific areas to several large, fairly located vote centers can be a net benefit to voters. Vote centers can have increased accessibility for people with disabilities, better facilities, the capacity to print ballots on site, and professional staffers working the polls. Levitt added that “an awful lot of this is on county officials for supplying the budget necessary to actually run elections… If county legislators cut [election administrators’] budgets, that’s going to mean they have to do more with less and that’s going to mean poll closures.”

Professor Levitt explained three things you can do to combat unfair poll closures. Levitt urged voters to engage more with county officials. “We need more attention paid to who local officials are… Learn who your local officials are. Learn who your election official is. Learn who your county legislators are,” Levitt said. Second, speak with local legislators about appropriating money for elections. Levitt added that county legislators “make money available for things that people are complaining about a lot because they like to be re-elected. And it turns out people only complain about the election process after the election and then they forget all about it before the next election.” Third, make sure you know where your polling place is. If your polling place is not in a convenient location, tell your local administrator. Levitt emphasized that “people can be involved in issues like this without needing to send a letter to the state capital.”

On the Ground Perspective: ACLU Georgia

Let America Vote spoke with Sean Young, Legal Director and Chris Bruce, Policy Counsel at ACLU Georgia. ACLU Georgia works with a coalition of organizations to fight against policies making it harder for Georgians vote.

“All voters deserve to be treated equally. However, polling place closures and consolidation frequently discriminate against voters of color. For example, in rural Irwin County, elected officials threatened to close the only polling place remaining in the one predominantly Black neighborhood in the entire county even though it was the most used polling place and located in the center of the county,” stated Sean J. Young, Legal Director for the ACLU of Georgia.

“Meanwhile, county officials kept open a polling place at the Jefferson Davis Memorial Park in a nearly all-white neighborhood. Only after we threatened litigation did the county officials withdraw their plans to close the precinct.”

In urban Fulton County, election officials voted to close-down those polling places but had given the public only six days-notice prior to the board’s upcoming vote. The ACLU of Georgia immediately filed a lawsuit and asked the court to nullify the board’s decision, because state law requires 14 days-notice to the public.

The Board of Registration and elections tried to sneak through plans to close several polling places in neighborhoods with 80%+ African American populations. The county elections board then admitted it had made a mistake, rescinded its decisions, and provided the 14-day notice.”

“The ACLU of Georgia worked alongside Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda, New Georgia Project, Georgia State Conference of the NAACP, Urban League of Greater Atlanta Young Professionals and Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law to mobilize the community to attend the next election board meeting,” stated Chris Bruce, Policy Counsel for the ACLU of Georgia. “Many community members testified that the poll closure jeopardized their fundamental right to vote. The board voted to keep open polling locations that are critically important to the Black and elderly community.

“Pressure from legal action coupled with public notice, a strong coalition that organized the community, and active citizen engagement ensured that the election board did its job,” Bruce stated. “These examples demonstrate being vigilant, organizing, and speaking out, together we can protect the sacred fundamental right to vote for all Georgians.”

Community Narrative: Macon-Bibb County and Fulton County

In Macon-Bibb County, the Board of Elections introduced a plan to consolidate the county’s 40 voting precincts into just 26. The board stated this would create cost savings, but most of the precincts that would be consolidated were majority-black. In fact, several of the majority-black precincts had over 5,000 and 6,000 voters, while not even one of the majority-white precincts had over 5,000 voters.[xx] Advocacy efforts stopped the Board’s plan; however, the Board still voted to lower the county’s precinct total to 33 — a move which advocacy groups argue still disproportionately affects the county’s black voters.[xxi]

In an article published the day after Election Day, Alice Speri documented all the chaos at the Macon-Bibb County polls.[xxii] Sheldon Brown went to three different polling locations until he was able to successfully cast a ballot. Sierra Scott showed up to a polling place with her father — he was allowed to vote there but she wasn’t, even though they live in the same home. Some dedicated voters went from polling place to polling place until they could cast a ballot. Others gave up and went home or simply weren’t able to find transportation to their polling site.

Another voter suppression tactic used in Macon-Bibb County and elsewhere ahead of the 2016 Presidential election was placing polling sites within a police station.

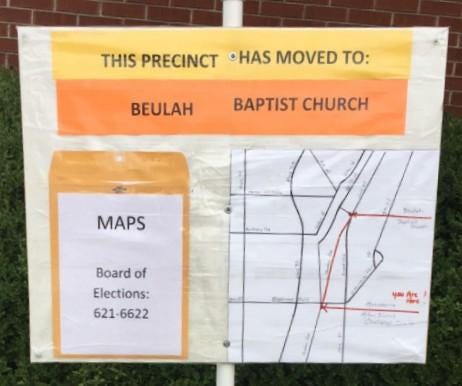

A polling place in a predominantly black neighborhood of Macon-Bibb County had to be moved from its usual gymnasium location due to renovations. The Board of Elections voted to move it to the county sheriff’s office. The local NAACP chapter president called this a blatant act of voter intimidation because of the county’s long history of conflict between the sheriff’s office and the local black community.[xxiii] The Board was forced to change the polling place to a nearby church after a petition drive that gathered signatures from 40 percent of local voters.[xxiv] But this nearby church was not even the final polling place. The Board of Elections moved it again and local leaders said most residents were never notified.[xxv] This raises another voter suppression tactic used in Georgia and elsewhere — last- second changes to polling places.

Recently, the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia sued the Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections for violating Georgia law. The Fulton County Board is required to give 14 consecutive days’ notice before approving any polling place change. But, just months before a major mayoral election, the Board of Elections voted to move or close several polling places located within predominantly black communities — after only six days notice. The ACLU of Georgia quickly filed a lawsuit requesting that the Court intervene and block the Fulton County plan.[xxvi] In response to the lawsuit, Fulton County elections officials reversed their decision and made no changes to polling places.[xxvii] Fortunately, there was enough time for the ACLU of Georgia to intervene. But decisions to change polling places often happen at the last minute, not allowing sufficient time for legal intervention.[xxviii]

Arizona: Closing Polling Places Creates Long Lines

Voters in Arizona’s Maricopa County experienced some of the longest lines of the 2016 cycle. Some Maricopa County voters waited more than 5 hours to cast a vote in the 2016 Presidential primary. The long wait times were likely due in part to the county’s decision to switch from 200 polling sites to just 60.[xxix] The waiting times were so problematic that the United States Department of Justice opened an investigation into what happened.[xxx]

Mayor Greg Stanton of Phoenix, Maricopa County’s largest city, argued that the plan to close the 140 polls disproportionately impacted people of color. He noted that in Phoenix, a majority-minority city, county officials allocated one polling place for every 108,000 residents, while another predominantly white community had one polling place for 8,500 residents.[xxxi]

Impact of Long Lines

Several studies have suggested that not only do long wait times at polling places lead to a decrease in voter participation, but longer waits also discriminate against people of color, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Professor Justin Levitt writes that some voters “are not physically able to remain on line. Still others must endure hours of lost wages or childcare expenses (if, indeed, childcare is available). Sometimes, the burdens of excessive lines are sufficient to deter participation entirely.”[xxxii] One recent study suggests that 11% of nonvoters chose to skip voting due to long lines — that number rose to 14.5% in 2012.[xxxiii] That same study showed that a lengthy wait at the polls decreases a voter’s likelihood to vote in future elections.[xxxiv] A study by Charles Stewart of MIT found that blacks and Hispanics waited nearly twice as long in line as whites.[xxxv]

A Different Path — Arizona

In 2017, the recently elected Maricopa County Recorder Adrian Fontes, implemented a new plan. During the 2017 election cycle, every Maricopa County voter received a mail-in ballot, not just those who requested one. These ballots were returned by mail, dropped off at a ballot center before Election Day, or given to a poll worker at a ballot center on Election Day. Recorder Fontes eliminated precinct voting altogether. In its place, there are countywide ballot centers in which any Maricopa County voter can cast a ballot.[xxxvi] Recorder Fontes believes this plan will not only cut costs and maintain a high level of voting security, but it will also reduce wait times throughout the county.[xxxvii] The Maricopa County plan shows that with proper planning and dedicated leaders, local officials can still save money on elections while increasing, not decreasing, access to the vote.

Voting Rights Advancement Act

In June 2017, Congresswoman Terri Sewell from Alabama’s 7th District introduced the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2017 (VRAA).[xxxviii] Congresswoman Sewell, whose district borders Shelby County, of the Shelby County v. Holder Supreme Court decision, said in a press release, “[O]ur work to prevent discrimination and protect the rights of all voters has taken on a new urgency. The time to restore the vote is now.”[xxxix] The VRAA creates a new coverage formula to replace the one found unconstitutional in Shelby County. Congresswoman Sewell explained that the bill, which measures a state’s discriminatory history, “examines the last 25 years — 1990 to present — as a way to put a modern-day formula on the enforcement of voting rights.”[xl]

The bill explicitly addresses the issue of poll consolidation, as well. Under the VRAA, if a poll change would occur in an area with a certain percentage of language or racial minority groups, that change would be subject to federal pre clearance.[xli]

What You Can Do

Monitor local newspapers to find out if polling places are closing or consolidating polling places in your area. If they are, and voters will be negatively impacted because of the closure or consolidation, testify at your local board of elections meeting, or meet with your county election director and express your concerns. Local coalitions of concerned citizens and advocacy groups have had success by working with local election officials, and have stopped polling place closures in Georgia and other states.

You can support the Voting Rights Advancement Act by urging your elected officials to support the bill. The protections of Voting Rights Act should be restored; the VRAA does exactly that. Passage of the VRAA is the right next step to protect access to the ballot for every American.

[i] Voting Rights Act of 1965, 89 P.L. 110, 79 Stat. 437.

[ii] Shelby County v. Holder, 133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013).

[iii] Scott Simpson, The Leadership Conference Education Fund, The Great Poll Closure 1–2 (Nov. 2016) http://civilrightsdocs.info/pdf/reports/2016/poll-closure-report-web.pdf[hereinafter The Great Poll Closure].

[iv] Id.

[v] ACLU, ACLU of Georgia Sues Fulton County Over Vote to Close Polling Places(July 18, 2017), https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-georgia-sues-fulton-county-over-vote-close-polling-places [hereinafter ACLU of Georgia Sues Fulton County].

[vi] Shelby County, 133 S. Ct. 2612, 2650 (2013).

[vii] Department of Justice, Jurisdictions Previously Covered by Section 5, https://www.justice.gov/crt/jurisdictions-previously-covered-section-5 (last visited Oct. 6, 2017).

[viii] Department of Justice, Voting Determination Letters for Georgia, https://www.justice.gov/crt/voting-determination-letters-georgia (last visited Oct. 6, 2017).

[ix] National Conference of State Legislatures, History of Voter ID (May 31, 2017) http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-id-history.aspx.

[x] Press Release, Common Cause, Common Cause, Georgia NAACP File Suit Challenging Voter Purges (Feb. 11, 2016) http://www.commoncause.org/press/press-releases/common-cause-georgia-naacp-sue-over-voter-purges.html?referrer=http://www.commoncause.org/search/?q=georgia.

[xi] Common Cause v. Kemp, 243 F. Supp. 3d 1315 (N.D. Ga. 2017) at 16.

[xii] Press Release, Common Cause, Common Cause and Georgia NAACP Appeal Lower Court Ruling Greenlighting Georgia Voter Roll Purge (Mar. 23, 2017) http://www.commoncause.org/press/press-releases/common-cause-and-georgia-naacp-voter-roll-purge-voting-rights.html.

[xiii] Brian Amos, Daniel A. Smith, & Casey Ste. Claire, Reprecincting and Voting Behavior, 38 Pol. Behav., no. 2, 2016 [hereinafter Reprecincting].

[xiv] See The Great Poll Closure, supra note 4.

[xv] Reprecincting, supra note 14.

[xvi] Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Georgia Fact Sheet: Voter Purges and Precinct Consolidations, (2016) https://lawyerscommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Georgia-Fact-Sheet-1.pdf [hereinafter Georgia Fact Sheet].

[xvii] Letter from Sean J. Young, Legal Director, ACLU of Georgia, to Irwin County Board of Elections & Registration (Apr. 21, 2017) https://www.acluga.org/sites/default/files/irwin_county_polling_place_demand_letter.pdf.

[xviii] Id.

[xix] ACLU, Irwin County Abandons Flawed Polling Place Plans After ACLU Demand (June 9, 2017) https://www.aclu.org/news/irwin-county-abandons-flawed-polling-place-plans-after-aclu-demand.

[xx] Georgia Fact Sheet, supra note 20.

[xxi] Laura Corley, Macon-Bibb has 7 fewer precincts this election cycle, Macon Telegraph (Oct. 5, 2015), http://www.macon.com/news/politics-government/election/article37836090.html.

[xxii] Alice Speri, In a Black Precinct in Georgia, Simply Finding the Polling Place Was a Challenge, The Intercept (Nov. 9, 2016), https://theintercept.com/2016/11/09/in-a-black-precinct-in-georgia-simply-finding-the-polling-place-was-a-challenge.

[xxiii] Id.

[xxiv] Id.

[xxv] Speri, supra note 25.

[xxvi] ACLU of Georgia Sues Fulton County, supra note 6.

[xxvii] Kristina Torres, Fulton County reverses controversial changes to polling sites, Atlanta J. Const. (Aug. 14, 2017), http://www.myajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/fulton-county-reverses-controversial-changes-polling-sites/nhkAPa2MpmxGeEI3yC45iI.

[xxviii] The Great Poll Closure, supra note 4.

[xxix] Jude Joffe-Block, Some Arizona Voters Cast Ballots After Midnight Due to Long Lines, KJZZ (Feb. 28, 2017), http://kjzz.org/content/282308/some-arizona-voters-cast-ballots-after-midnight-due-long-lines.

[xxx] Spencer Woodman, Budget Cuts Are Robbing Americans of Their Voting Rights, Vice (Apr. 14, 2016), https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/ppvywk/how-counties-across-america-are-defunding-voting-rights.

[xxxi] Letter from Greg Stanton, Mayor, City of Phoenix, to the Honorable Loretta Lynch, Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice (Mar. 23, 2016) https://www.phoenix.gov/mayorsite/Documents/Mayor Greg Stanton Letter to DOJ.pdf.

[xxxii] Justin Levitt, “Fixing That”: Lines at the Polling Place, 28 J.L. & Politics 465, 467 (2013).

[xxxiii] Stephen Pettigrew, How long lines affect minority precincts, 7 (Mar. 3, 2015) https://wpsa.research.pdx.edu/papers/docs/wait times paper.pdf.

[xxxiv] Id. at 1, 21–24.

[xxxv] Charles Stewart III, Waiting to Vote in 2012, 28 J.L. & Politics 439, 457–58 (2013).

[xxxiv] Id. at 1, 21–24.

[xxxv] Charles Stewart III, Waiting to Vote in 2012, 28 J.L. & Politics 439, 457–58 (2013).

[xxxvi] 2017 election plans outlined, Fountain Hills Times (July 31, 2017), http://www.fhtimes.com/news/local_news/election-plans-outlined/article_c882f554-7183-11e7-af9f-2bedcf5a181e.html.

[xxxvii] Steve Goldstein, Big Changes Coming for Voters in Maricopa County, KJZZ (June 21, 2017), http://kjzz.org/content/494038/big-changes-coming-voters-maricopa-county.

[xxxviii] Press Release, Congresswoman Terri Sewell, Rep. Sewell Introduces Voting Rights Advancement Act at #RestoreTheVOTE Speak Out (June 22, 2017) (https://sewell.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/rep-sewell-introduces-voting-rights-advancement-act-restorethevote-speak).

[xxxix] Id.

[xl] Katanga Johnson, House Democrats Seek Voting Rights Act Improvements, U.S. News (June 22, 2017), https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2017-06-22/house-democrats-move-to-restore-key-provisions-of-the-voting-rights-act.

[xli] Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2017, H.R. 2978, 115th Cong. (2017).